In real-time simulations and games, rendering and gameplay require significantly greater dedication of CPU, GPU, and texture memory compared with user interfaces (UI). Therefore, UI is typically allocated a smaller portion of the performance budget compared to other systems, and these budgetary constraints are most often felt on devices with limited resources. This makes it important to use those resources as efficiently as possible and reduce resource consumption in your UI wherever possible.

While your UI's needs depend on the details of your project and your target platform, there are some guidelines for optimization you can follow when building a UI with Slate and UMG in Unreal Engine. This page provides an overview of these best practices, including:

- Optimization features that can reduce your performance footprint.

- Guidelines on the most CPU-intensive widgets.

- Information about what to avoid when building your UMG layout.

- An overview of the CPU cost of different methods of animation in UMG.

For general information about optimization and profiling, refer to the following pages:

Invalidation

Invalidation caches Slate widgets' information, then monitors them for changes that invalidate their paint, layout, or hierarchy information. As long as a widget does not change, Slate falls back on the cached information instead of repainting the widget. When a change invalidates this information, Slate re-calculates it and repaints the widget.

Unreal Engine supports several methods for incorporating Invalidation into your UI:

- Invalidation Boxes cache the information of their child widgets.

- Global Invalidation treats the entire

SWindowas an Invalidation Box, applying Invalidation to your entire UI.` - Retainer Panels flatten their child widgets into a single texture before painting them, and provide options for configuring their framerate or delaying rendering.

Invalidation is most effective for groups of widgets that do not change often, effectively freeing up the CPU load that would be spent repainting them each frame at the cost of memory. Widgets that change on a frame-by-frame basis should be marked as Volatile to prevent them from needlessly caching information, as they will repaint every frame anyway.

For more information about these systems, details about how to implement them, and their limitations, refer to Invalidation in Slate and UMG.

Programming and Scripting

The following are best practices for programming within UMG's environment.

Use On-Tick or On-Paint Logic Sparingly

Whenever possible, you should avoid using On Tick or On Paint to run logic in your UI. Event Dispatchers and Delegates can help you create logic that responds to specific events without needing to rely on Tick.

Use Event-Driven Updates Instead of Bound Attributes

When you bind attributes to fields in your UI, they poll the attribute every frame. For example, if you bind the Text value of a Text Field to an integer, that Progress Bar will assign the integer's value to that field every tick. This is inefficient, so you should avoid using bound attributes.

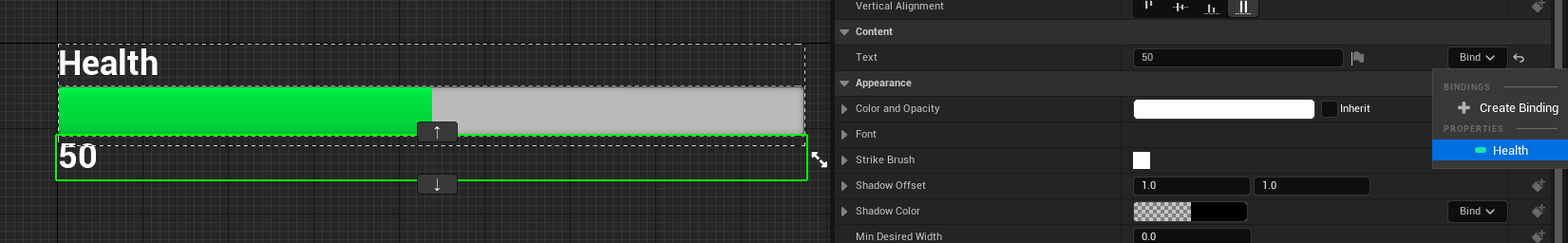

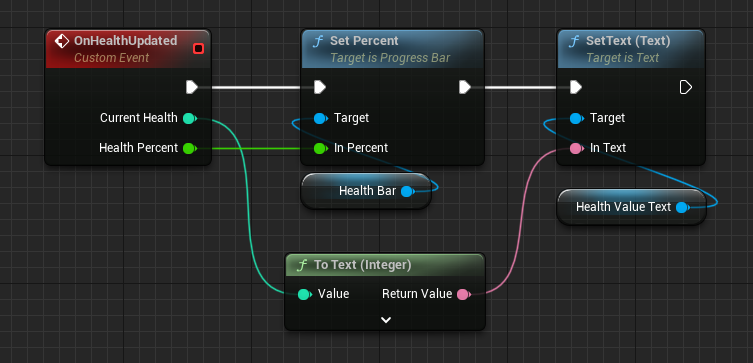

Never use raw attribute binding.

Instead, you should set up your project to call functions and events in your UI to update these fields. For instance, instead of binding a health bar to a Health attribute, you should call an OnHealthChanged event in your UI's Blueprint script to change the necessary fields in your UI.

An example of updating the UI with an event.

While setting these up is more time consuming, this ensures that the UI only changes on the frame when the value changes instead of each frame.

Loading and Construction

The following are best practices for structuring widgets and building them at runtime.

Reduce Unused Widgets As Much as Possible

All children inside a widget are loaded and constructed regardless of whether they are visible. Even if your UI does not render them, they will use memory and require loading and construction time.

At a basic level, your UI designers should regularly check for any unused widgets and remove them before committing their work. Regular cleanup will help with organization as well as performance.

Break Complex Widgets Into Pieces that can Load at Runtime

An especially complex widget for a major system could have well over 1000 children to handle all of its functionality, but only need to display a few hundred widgets at a time. In these situations, if you were to load the entire widget as one big piece, hundreds of inactive children would take up space without being used. Depending on how specialized these child widgets are, users may spend hours without seeing them.

In these cases, you should break up your widgets into categories:

-

Widgets that are always visible.

-

Widgets that must be shown as quickly as possible.

-

Widgets that can afford to have a small amount of latency when shown.

Any widgets that require fast response times should be loaded in the background even when not displayed. For example, an inventory screen in a competitive shooter is used very frequently and should be highly responsive due to its crucial function for the player, so keeping it loaded but not visible is good practice.

Any widgets that are not present for long periods of time and do not require fast response should be loaded asynchronously at runtime and destroyed when dismissed. For complex widgets with diverse functions, this may entail keeping a base widget loaded at all times, but loading different sets of child widgets asynchronously depending on what mode or function is needed. This can save a great deal of memory and reduce the CPU impact on initialization.

Layout and Positioning

The following are guidelines for improving the efficiency of your widgets when building your UI's layout.

Use Canvas Panels Sparingly

The Canvas Panel is a powerful container widget that can position other widgets using a coordinate plane and per-widget anchors. This makes it easy to both position widgets exactly where you want them, and also to maintain widgets' positions relative to the corners, edges, or center of the screen.

However, Canvas Panels also have high performance demands. Draw calls in Slate are grouped by widgets' Layer IDs. Other container widgets, such as Vertical or Horizontal Boxes, consolidate their child widgets' Layer IDs, thus reducing the number of draw calls. However, Canvas Panels increment their child widgets' IDs so they can render on top of one another if need be. This results in Canvas Panels using multiple draw calls, thus making them highly CPU-intensive compared with alternatives.

Overlay panels also increment their Layer IDs, and therefore also use multiple draw calls. These are less likely to have the same impact as Canvas panels due to the more limited scope that they are used in by comparison, but keep this in mind when using Overlays as well.

Using one Canvas Panel to lay out the root widget for a HUD or menu system should not be a problem, as these are instances when you would most likely need detailed positioning or complex Z-ordering. However, you should avoid using them to lay out individual custom widgets like text boxes, custom buttons, or other templated elements. This results in nesting Canvas Panels multiple layers deep throughout many elements in your UI, which is extremely resource-intensive. Furthermore, excessive use of Canvas Panels in multiple layers can make it confusing to discern which layer of your UI is responsible for determining part of the final layout.

As a rule of thumb, if your widget consists of a single element, you definitely do not need a Canvas Panel. Even with full menus and HUDs, you can often avoid using Canvas Panels altogether by using Overlays and Size Boxes together with Horizontal, Vertical, and Grid Boxes to handle layouts.

Use Spacers Instead of Size Boxes When Possible

Size Boxes use multiple passes to calculate their size and render themselves. If you need content to take up a certain size in width and height, Spacers are significantly cheaper.

Avoid Combining Scale Boxes and Size Boxes

If you combine Scale Boxes and Size Boxes, they will try to update each other and get stuck in a loop, flipping between two sizes each frame. Instead of relying on either of these, you should try to make your layout work according to the native size of your content.

Use Rich Text Widgets Sparingly

Rich Text widgets provide robust formatting for text, but are very expensive compared with standard text boxes due to the wide range of extra capabilities they add. If you want text to be stylized or expressive, but do not need the full functionality of rich text, you should choose or create a font that reflects the sense of stylization you want by default and fall back on standard Text widgets.

Animation Costs

There are several approaches for animating widgets at runtime. When working with Invalidation, some of these methods can cause widgets' layouts to invalidate, which causes entire branches of the hierarchy to be re-updated. The following table lists these animation methods and their relative CPU cost in UMG:

| Cost | Examples |

|---|---|

| No CPU Cost/Least Expensive | Material-only animations. |

| Low CPU Cost | Blueprint-scripted animations that do not require Sequencer. |

| High CPU Cost | Sequencer animations made with UMG's animation editor. |

| Most Expensive CPU Cost | Animations that cause layout changes. |

Material-only animations incur no CPU cost as these are handled by the GPU. These are preferable for looping animations like glow effects, scrolling backgrounds, or other effects that could be represented with a material change. If it is possible to contain an animation to a material, you should favor this method over all others.

UMG's animation editor is an implementation of Sequencer. Any Sequencer animations that change non-transform attributes, such as color, will require the widget to be redrawn, but they won't invalidate the layout. Any animation that causes changes to the render transforms will cause layout invalidation, which will in turn recalculate the layout each frame that the animation changes the widget. You should either avoid this, or mark any widgets that require this kind of animation as Volatile.

Blueprint-scripted animations and Sequencer animations have roughly equivalent running costs, but Sequencer animations must initialize an animation object and resolve the property paths the animation is responsible for before they start animating. This means Sequencer animations incur a startup cost that Blueprint-scripted animations do not. Therefore, when you are working with short, frequently-used animations, such as animated damage numbers, you should avoid using Sequencer and rely on Blueprint-scripted tweens instead.